|

Negro Folk Symphony The Bond of Africa: Adagio--Allegro con brio |

Composed: 1934; rev. 1952 Estimated length: |

|

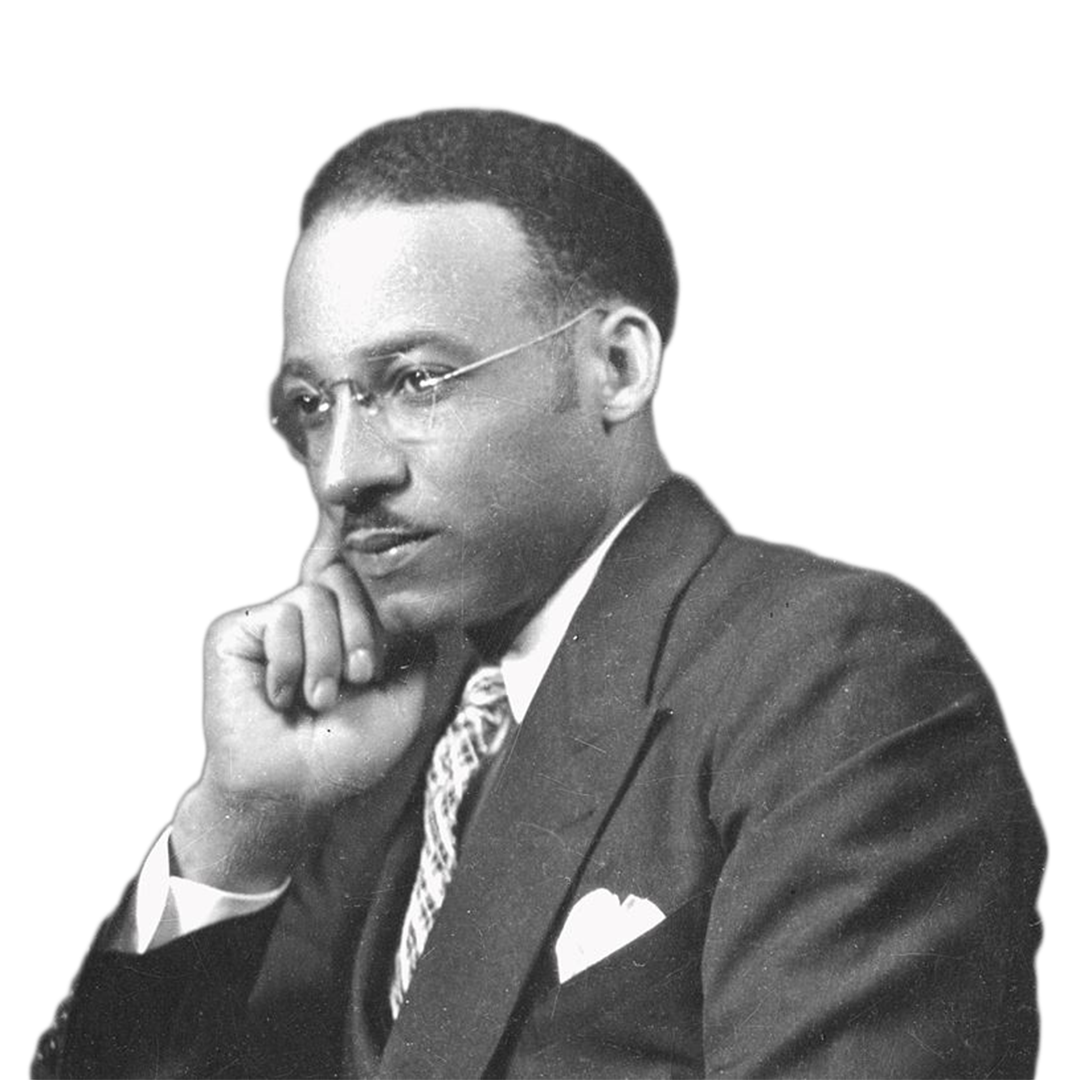

Born on September 26, 1899, in Anniston, Illinois; Died on May 2, 1990, in Montgomery, Alabama |

|

|

First performance: November 20, 1934, with Leopold Stokowski conducting the Philadelphia Orchestra. |

|

|

First Nashville Symphony performance: These are the Nashville Symphony's first performances of this work. |

|

"The most distinctive and promising American symphonic proclamation which has so far been achieved,” wrote the critic Leonard Liebling following the Carnegie Hall premiere of the Negro Folk Symphony in 1934. And it was not just the critics who were impressed. The audience broke into an enthusiastic ovation after the second movement, causing the musicians to stand to acknowledge the reaction. Led by the celebrity conductor Leopold Stokowski, the performance was broadcast across the nation.

A sea-change toward greater inclusivity might have taken hold in those years, which also saw the premieres of Florence Price’s Symphony No. 1 and William Grant Still’s Afro-American Symphony. Yet that failed to happen. William Levi Dawson, only 35 at the time—he had been born on the cusp of the new century in northeast Alabama—would never return to the genre of the symphony, despite living nearly six more decades.

Influenced by his musical impressions during a tour to West Africa in the 1950s, Dawson later made substantial revisions to the score, which was then recorded by Stokowski. But he turned his attention mostly to his educational commitments, as well as to his widely performed choral arrangements of African American spirituals. It wasn’t until our era that reassessment of Dawson’s achievement, as with that of Florence Price, prompted efforts to include his music in the repertoire.

The musicologist and pianist Gwynne Kuhner Brown, an authority on the composer, explains that although the the word “Negro” in the title is “uncomfortable to many today,” it was “for Dawson and others of his generation a term of pride and respect … Throughout his life, in his teaching and his music, Dawson extolled the culture and history of his race.”

The Negro Folk Symphony is cast in three movements that trace a journey on multiple levels: the explicit one of the harrowing passage of those kidnapped from Africa and forcibly taken to the New World to be enslaved, but also an implicit journey of the self.

WHAT TO LISTEN FOR

The first movement (“The Bond of Africa”) gives a prominent role to the solo horn: in the introduction, it plays a core motif that binds the work together and represents “a link [that] was taken out of a human chain when the first African was taken from the shores of his native land and sent to slavery,” as Dawson describes it. The pathos of the slow opening gives way to a more animated atmosphere, but the mood is not unequivocal.

Negro Folk Symphony incorporates ideas derived from several spirituals, except for the central movement (“Hope in the Night”): according to Brown, Dawson’s omission here is a way of “denying listeners the comfort of imagining the enslaved finding solace in religion.”

The composer wrote of depicting “the characteristics, hopes, and longings of a Folk held in darkness,” in the first section, which is contrasted with an image of “children, unmindful of the heavy cadences of despair … but even in their world of innocence, there is a little wail, a brief note of sorrow.” The sense of hope is hedged by doubt, especially in the final measures. But a more sustainable joy emerges in the final movement (“O Le’ Me Shine, Shine Like a Morning Star!”). The revised version of this music shows the influence of complex rhythmic structures Dawson had encountered on his travels in Africa.

Scored for piccolo, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, English horn, 3 clarinets, bass clarinet, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, harp, and strings

− Thomas May is the Nashville Symphony's program annotator.