|

Symphony No. 4 in B-flat major, Op. 60 Adagio - Allegro vivace |

Composed: Estimated length: |

|

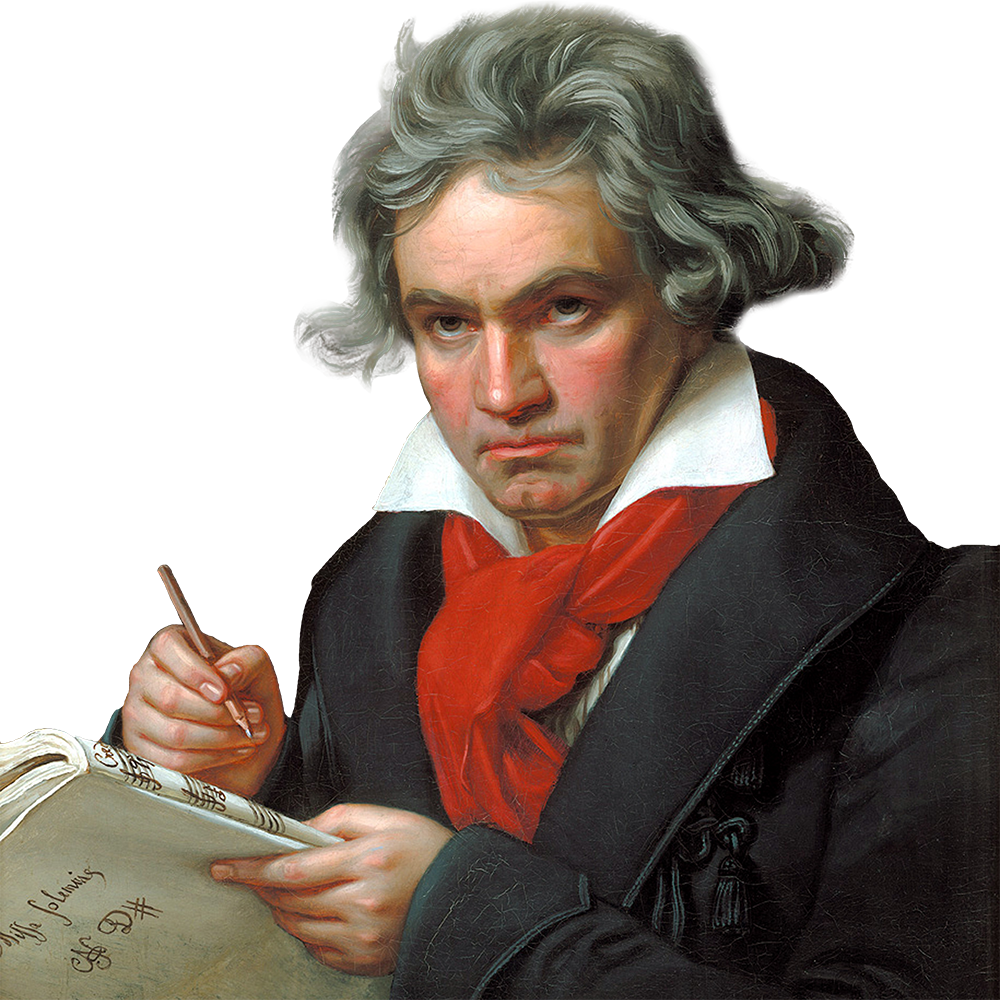

Born on December 16, 1770, in Bonn (in present-day Germany); Died on March 26, 1827, in Vienna, Austria |

|

|

First performance: March 1807, with the composer conducting a private performance in the palace of Prince von Lobkowitz, the dedicatee. |

|

|

First Nashville Symphony performance: December 20, 1949, with William Strickland conducting at the Ryman Auditorium. |

|

Robert Schumann, among the most perceptive of the post-Beethoven generation of admirers, likened the Symphony No. 4 to “a slender Greek maiden between two Norse giants.” Colorful as the image may be, it packs a lot of politics and aesthetic bias into Schumann’s attempt to account for the fact that the Fourth Symphony sounds so strangely different from its companion symphonies.

Those “Norse giants,” in fact, are themselves vastly different from each other: the Eroica (Third Symphony) a sprawling epic and the Fifth a taut, tragic orchestral drama. Schumann overlays his stereotypical gender coding with allusions to two different pagan outlooks: Greek antiquity versus Nordic myth.

But when we approach the Fourth Symphony without the burden of these biases—and the same is true for the Eighth—it opens up a wider understanding of Beethoven’s process. His originality was not confined to what the exaggerated image of the defiant rule-breaker would have us believe but took other forms as well—forms that in no way subtract from the revolutionary character of the celebrated milestones.

What is true across all nine of the symphonies is that the search for new and different solutions preoccupied Beethoven persistently. He had already begun working on what became the Fifth Symphony when he put that project aside to compose the Fourth in the summer and fall of 1806, to fulfill a commission from Count Franz von Oppersdorff, a new patron particularly fond of his Second Symphony. One theory holds that Beethoven opted for a relatively conservative and accessible style to indulge the Count’s taste, planning to return to the more overtly innovative Fifth after securing his fee.

In certain other scores, Beethoven shows that he was perfectly capable of detaching himself, producing inconsequential music to order. But the stakes were too high when it came to the genre of the symphony. The Fourth may not be as aggressively radical as its neighbors, but it contains subtle innovations and audacities of its own.

Another way of putting it: if Beethoven looks more closely to the models he inherited from his predecessors, it is to consider fresh ways to outdo them. Haydn, though still alive, had long since ceased to write symphonies, and Beethoven both coopted and challenged what he learned from his revered elder with renewed vigor.

WHAT TO LISTEN FOR

Beethoven expands the slow introduction into a mini-drama. The first four notes in the violins are variants of the intervals of the “Fate” motif that opens the Fifth Symphony. But heard in slow motion here—as opposed to the hurtled-against-the-wall fury of the Fifth—they evoke an atmosphere of extraordinary suspense and mystery. The Allegro vivace bursts on the scene with a blazing, white-hot light.

In the slow movement, Beethoven plays a mechanically repetitive rhythmic idea off one of the most ingratiating melodies he ever conceived. Characteristically, the tune is little more than a glorified descending scale followed by a resolution. Beethoven’s old-fashioned title for the third movement (“Minuet”) almost seems ironic in view of his abrupt rhythmic jolts, exaggerated contrasts of loud and soft, and odd harmonic shifts. The easygoing, regular meter in the middle of the movement only underscores the joke—a comic pose of naïvete to offset the rhythmic ingenuity surrounding it.

Beethoven wanted to outdo Haydn, but he also paid tribute to the tricks he learned from his former teacher, nowhere more so than in the finale—a virtual comic opera of hysterically bustling humor. The theme chugs in perpetual motion—allowing Beethoven to stage a near “train wreck” at one point when the bassoon seems to get the timing wrong. The Fourth encompasses yin and yang, shadow and light—all capped by a final, resounding joke.

Scored for flute, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, timpani, and strings

− Thomas May is the Nashville Symphony's program annotator.